Who is online?

In total there are 4 users online :: 0 Registered, 0 Hidden and 4 Guests None

Most users ever online was 77 on Wed Nov 20, 2024 3:31 pm

Top posting users this month

| No user |

The Life and Death of the Original Xbox

Page 1 of 1

The Life and Death of the Original Xbox

The Life and Death of the Original Xbox

It's March in 1999 and Sony is a year away from releasing its

recently announced PlayStation 2. From a technological standpoint, the

PS2 is a peerless powerhouse. Early demos showcase incredible 3D visuals

and beautiful animation. Sony talks about modem support and DVD

playback. This is the future of gaming, and we haven't seen anything

like it.

Meanwhile, four dudes at Microsoft's Redmond, WA fortress are working on

a future of their own. Kevin Bachus, Seamus Blackley, Otto Berkes, and

Ted Hase want to create the company's first gaming console. Looking

ahead, they see more for video games than higher polygon counts. Their

idea would facilitate creative growth, not just fancier visuals. They

pitch their idea straight to Bill Gates. Unless Microsoft can do

something to differentiate its product from the rest, outdo its

competitors, and contribute to the industry in a meaningful way, Gates

isn't sure it's a good idea.

He hears 'em out.

He changes his mind.

The Xbox would grow to become synonymous with gaming and cement Microsoft as a key player in the industry.

The Xbox would grow to become synonymous with gaming and cement Microsoft as a key player in the industry.

For the following year, the newly formed console team, joined by

Microsoft Game Studios head honcho Ed Fries, talked to developers about

what they wanted to do with console gaming. Existing hardware holding

back big ideas was a running theme. The conclusion Microsoft walked away

with was this: If consoles stifled creativity, games would only see

major breakthroughs on the ever-evolving and far more flexible PC. That

had to change, and the solution was obvious. Microsoft would build a

badass gaming rig and put it in our living rooms.

So what would the guts of its "DirectX Box" -- quickly abbreviated to

just Xbox -- look like? Microsoft would run it on its own operating

system, of course, using the Windows 2000 kernel. The Xbox would also

use (and derive its name from) DirectX 8, a suite of special software

systems programmers used to talk to the internal hardware. This way,

studios familiar with PC game development (BioWare, Lionhead, and Red

Storm, for instance) could understand the architecture without much

fuss. Ideally, the exciting opportunities of a new platform would also

be easy to work with. This is a luxury many new and complex consoles

aren't afforded. With the Xbox foundation in place, the remaining

hardware specifications became a matter of would make Microsoft's

machine-dreams come true.

After meeting with many suitors, Microsoft struck a deal with Nvidia,

whose audio and graphics components would work alongside an Intel

Pentium III core processor. At 733 MHz, the 32-bit CPU had more than

double the PlayStation 2's processing power and worked with twice the

RAM (64MB rather than the PS2's 32). Add an 8GB hard-disk drive to this

impressive set of tech specs and you'd have what's easily the most

powerful and able home console conceived. It had all the necessary parts

to support its grand ambitions while enabling a stronger visual output

than its competitors. The Xbox was born -- now to tell the world about

it.

Bill Gates took the stage at the Game Developers Conference in 2000 to

formally announce the Xbox. He detailed the future of console gaming

with the Xbox leading the charge. At the time, online gaming on consoles

was both unsuccessful and relatively unknown. The Dreamcast

experimented with a modem adapter, but broadband support out of the box,

a priority for the Xbox from day one, was unheard of. Downloading

additional game content and demos was another foreign concept for

console gamers. Storing this media, as well as music ripped from CDs, on

an internal hard drive was also new. This was a console, we'd play it

on our couch, and we'd use controllers -- but it sure sounded like a

personal computer in terms of what it was capable of.

The original Xbox blurred the line between console and PC.

The original Xbox blurred the line between console and PC.

It was important to Microsoft that these PC features and standards not

overshadow the importance of bringing a brand-new console to our

attention. The Xbox design had to look as unlike a PC as possible. After

all, Microsoft was a consumer company in addition to a hardware and

software corporation now. The prototype model shown at GDC in 2000 was a

chrome cube carved into a literal X. It was a dramatic departure from a

computer case, that's for sure. Silly though it may have been, it made a

clear point: Microsoft's Xbox isn't just another gaming system. Things

would be different.

Shortly after GDC, Microsoft cemented its commitment to the Xbox with

its $30 million purchase of Bungie Studios. Its Halo: Combat Evolved

transformed from a Mac/PC third-person shooter to an Xbox-exclusive FPS.

Halo would take advantage of the Xbox's expanded hardware to present an

action game unlike any we'd seen before. The world would be massive in a

way that wasn't possible on other systems. Bungie overhauled the game's

engine to better suit its new platform, and it became the platform's

poster child. The allure of the Xbox was stronger each day leading up to

its 2001 launch.

It was hard not to notice the Xbox, really. With a $500M marketing

budget, Microsoft wasn't pulling any punches with its new device. Demo

kiosks, TV spots, and print ads made up the bulk of Microsoft's

marketing materials. 165 companies had been tinkering with some 2,250

development kits, and the future of the Xbox looked bright in their

hands. In addition to new IPs like Project Gotham Racing and Halo,

Tecmo, Sega, and Capcom showed Japanese support for the platform with

exclusives of their own. Munch's Odyssey and Malice demoed well at the

2001 Consumer Electronics Show as well, where Gates unveiled the final

Xbox model we'd see in fall that year. By E3, we had a release date, a

$299 price-point, and a vague understanding that online gaming would

come after what became a monumental launch for Microsoft.

November 15, 2001 marked the company's first console release, and Halo,

its premier first-party title, shattered software sales records. By the

New Year, the Xbox had sold out nearly everywhere and 1.5 million of the

big, black crates found their way into North American homes. Halo

continued to crush the competition, it was moving full steam ahead. By

April it had cracked one million copies sold, and gained a greater than

50% attach rate.

(Fun fact: Halo sold 5M units by 2005, which was gigantic. How times

change -- in 2011, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 sold 6.5M in its first

24 hours.)

With the Xbox exploding, 2002 looked like a hell of a year. The system

launched in Europe and Japan, and excitement swelled for Splinter Cell,

MechAssault, and The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind. Microsoft made big waves

when it purchased Rare, whose Banjo Kazooie and Goldeneye games were

arguably the pinnacle of Nintendo 64 gaming, for an astonishing $375M.

Oh, and a little sequel called Halo 2 was on the horizon. The industry

was buzzing because of Xbox, and it still hadn't even done what it was

truly meant to do -- we were still only seeing developers scratch the

surface of what great-looking games could really do, and the upcoming

online service had only hinted at its potential. Xbox Live was about to

knock the industry on its ass.

Xbox LIVE was a huge milestone for digital gaming.

Xbox LIVE was a huge milestone for digital gaming.

This particular launch wasn't exactly extravagant. At the tail end of

August 2002, Microsoft began its Xbox Live beta test. This whole "online

gaming" thing was so unfamiliar and unproven on consoles it had to be

put through its paces prior to going public. Of more than 100,000

applicants, a lucky 10,000 gained 60 days of early access. Even then,

the limited invitations rolled out in small groups over the course of

those couple months. It had to be done delicately.

Beta testers paid $49.99 for the Xbox Live Starter Kit we'd all see in

November. Along with a headset and a year subscription, which began once

Live went live, users received an online-only demo of the RC car racer,

Re-Volt Live. The Dreamcast port didn't end up on the Xbox after the

test cycle. Weeks later, some time in October, participants also

received MotoGP and Whacked! demos. These also wound up packed in with

the first wave of Starter Kits.

Things looked good by November 15, the Xbox's first birthday, and

Microsoft launched Xbox Live to the masses. In its first week, 150,000

enthusiastic gamers took the plunge and signed up for Xbox Live. 200,000

additional players joined them four months later. Everyone could send

messages and create a unified friends list, which linked to their

Gamertag ID. People were interacting with other human beings from their

living room for the first time, making friends, and experiencing

multiplayer on a new scale. This was a community, not just a bunch of

customers. Oh, and gamers finally had an Xbox controller they could use

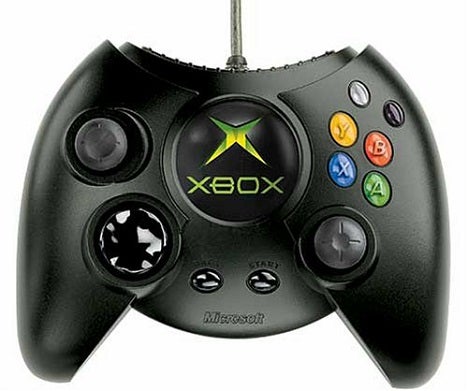

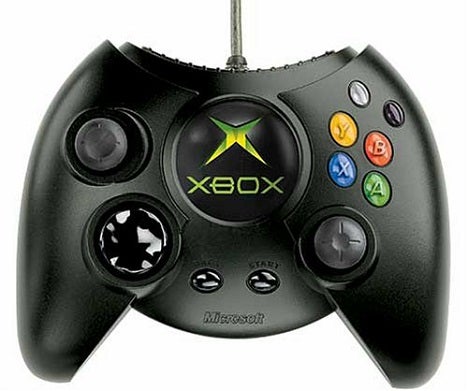

effectively. The Japanese "S" model, a smaller, decidedly Dual

Shock-esque version of the game pad, replaced the clumsy, gigantic

"Duke" model permanently.

"Duke" was big, clumsy, and eventually replaced, but some of its design choices remain to this day.

"Duke" was big, clumsy, and eventually replaced, but some of its design choices remain to this day.

Over its lifetime, Microsoft's Xbox, despite its success, had some

powerful lows. Bachus left the Xbox team in 2001 (before the thing had

even launched) and Blackley bailed the following year. In 2003, EA opted

against enabling its games for Xbox Live. The mammoth

developer/publisher wasn't keen on the business practice of a

subscription-based online service, so it stuck with Sony. The

PlayStation 2 would be the only place gamers could play Madden online.

This was a harsh blow to Microsoft, but the two companies sorted out

their differences. They reached an agreement in 2004 that brought EA

support to the Xbox online space. This good news came shortly after Ed

Fries, who was responsible for the Bungie and Rare buyouts, left

Microsoft. The Xbox needed a pick-me-up something fierce.

In July 2004, Microsoft hit a huge milestone: Xbox Live had one million

users, 200 pieces of downloadable content, and more than 100

online-enabled titles. An unprecedented digital distribution service

called Xbox Live Arcade was on track for winter as well, and with Halo

2's advertising campaign kicking into full force, the Xbox looked like

it was ready to rock once again.

Halo 2 was an event. The time leading up to the game's release saw the

exposure and marketing storm typically reserved for, well, the launch of

a brand new console. Bungie's sequel had print ads, posters plastered

on public transportation, TV commercials, 7-11 slurpee cups got the

public's blood pumping, while a viral marketing campaign -- the infamous

I Love Bees

-- excited online enthusiasts. It was money and time well, spent,

apparently. On November 9, 2004, Halo 2 generated $125M in sales, based

on nearly 2.5M copies sold, more than half of which were pre-orders. It

destroyed the record its predecessor set. Equally impressive are the

other properties it outdid -- Harry Potter, Spider-Man, and The Matrix

fell beneath Master Chief's big green boots. Halo 2 was the biggest

entertainment launch in history, and it became what Microsoft rightfully

referred to as "a cultural phenomenon."

Halo 2's I Love Bees campaign was an early example of successful viral marketing in the gaming industry.

Halo 2's I Love Bees campaign was an early example of successful viral marketing in the gaming industry.

Here's the thing about the Xbox up to this point: It wasn't making any

money. It haemorrhaged cash so badly and for so long that it didn't turn

its first profitable quarter until the back end of 2004. From the

start, the Xbox cost more to make than it did to sell, which is what

makes this so shocking: six months after launch Microsoft dropped the

price by $100 to get more gamers on board with Xbox. It had to rely on

software sales to make bank.

Also, the Xbox was failing in Japan. Not just tanking, either -- it had

died almost instantly. The console's gigantic size, which goes against

the country's small-and-sleek design mentality, is a prime suspect for

its miserable 450,000 sales. Most likely, though, it's the lack of

Japanese developer support, and few games Japanese gamers actually

wanted to play, that killed the brand in Japan. The early dev support

from the east didn't last, and American developers dominated the Xbox

releases. The appeal wasn't there.

With an Xbox successor on its mind behind the scenes for some time,

Microsoft wasn't focusing on its floundering console. When Xbox

manufacturing ceased in 2005, after Nvidia stopped bothering to press

more GPUs, Microsoft was revving up to release the Xbox 360. It made

sense to press on. The Xbox sold respectably well in bursts, but in the

end only 24 million pieces of hardware (16M of which belonged to North

America) moved in its five years. That's half the 50M-units-sold success

Microsoft expected. At the same time, Sony had sold 106 million PS2s.

All told, Microsoft lost an astounding $4 billion -- yeah, with a B --

on the Xbox. That's a lot of money to just leave behind, especially

when the Xbox had so many obvious strengths. It just wasn't able to

capitalize on them like a newer machine could.

In November 2005, just four years after the Xbox hit retail, Microsoft

unloaded the Xbox 360. This time, it would release ahead of Nintendo's

and Sony's newest consoles. Microsoft was the only name on our minds as

we moved into the next generation, giving the successor the early

adopter monopoly. While Microsoft left its failed first attempt behind,

the original Xbox maintained an impressive amount of developer support.

Halo 2, of course, grew into the biggest game on the platform, both in

terms of players and sales. It earned more than 8M sales, and Bungie

released downloadable Halo 2 maps around the time Xbox Live had six

million members. EA, ironically, supported the platform the longest. The

last original Xbox release, Madden 09, landed in August, 2008.

Behold the very last game for the original Xbox.

Behold the very last game for the original Xbox.

Although developers migrated their attention to the new Xbox, and many

studios shut down individual game servers over the years,

Counter-Strike, Star Wars: Battlefront, and Halo 2 still had an

impressive, active user-base for years after the 360 came around. The

original Xbox had a heartbeat until April 14, 2010. This day marks the

death of Xbox Live support.

It also marks the moment where we were forced to let go of something

that changed a lot of lives, and turned the industry upside down. The

Xbox was ahead of its time, and Microsoft paid the price for it. While

it failed financially, it was a worthwhile sacrifice for both Microsoft

and the gaming industry. The Xbox had so many important ideas early on

that they've since become the modern standard. This thing changed what

we expect from games. It represented progress and forward-thinking, and

it demanded innovation from its competitors to keep up. This is a

philosophy that carried over to the Xbox 360, and is responsible for

many wonderful things we adore about the industry today.

Thanks for entertaining the idea, Bill.

recently announced PlayStation 2. From a technological standpoint, the

PS2 is a peerless powerhouse. Early demos showcase incredible 3D visuals

and beautiful animation. Sony talks about modem support and DVD

playback. This is the future of gaming, and we haven't seen anything

like it.

Meanwhile, four dudes at Microsoft's Redmond, WA fortress are working on

a future of their own. Kevin Bachus, Seamus Blackley, Otto Berkes, and

Ted Hase want to create the company's first gaming console. Looking

ahead, they see more for video games than higher polygon counts. Their

idea would facilitate creative growth, not just fancier visuals. They

pitch their idea straight to Bill Gates. Unless Microsoft can do

something to differentiate its product from the rest, outdo its

competitors, and contribute to the industry in a meaningful way, Gates

isn't sure it's a good idea.

He hears 'em out.

He changes his mind.

The Xbox would grow to become synonymous with gaming and cement Microsoft as a key player in the industry.

The Xbox would grow to become synonymous with gaming and cement Microsoft as a key player in the industry.For the following year, the newly formed console team, joined by

Microsoft Game Studios head honcho Ed Fries, talked to developers about

what they wanted to do with console gaming. Existing hardware holding

back big ideas was a running theme. The conclusion Microsoft walked away

with was this: If consoles stifled creativity, games would only see

major breakthroughs on the ever-evolving and far more flexible PC. That

had to change, and the solution was obvious. Microsoft would build a

badass gaming rig and put it in our living rooms.

So what would the guts of its "DirectX Box" -- quickly abbreviated to

just Xbox -- look like? Microsoft would run it on its own operating

system, of course, using the Windows 2000 kernel. The Xbox would also

use (and derive its name from) DirectX 8, a suite of special software

systems programmers used to talk to the internal hardware. This way,

studios familiar with PC game development (BioWare, Lionhead, and Red

Storm, for instance) could understand the architecture without much

fuss. Ideally, the exciting opportunities of a new platform would also

be easy to work with. This is a luxury many new and complex consoles

aren't afforded. With the Xbox foundation in place, the remaining

hardware specifications became a matter of would make Microsoft's

machine-dreams come true.

After meeting with many suitors, Microsoft struck a deal with Nvidia,

whose audio and graphics components would work alongside an Intel

Pentium III core processor. At 733 MHz, the 32-bit CPU had more than

double the PlayStation 2's processing power and worked with twice the

RAM (64MB rather than the PS2's 32). Add an 8GB hard-disk drive to this

impressive set of tech specs and you'd have what's easily the most

powerful and able home console conceived. It had all the necessary parts

to support its grand ambitions while enabling a stronger visual output

than its competitors. The Xbox was born -- now to tell the world about

it.

Bill Gates took the stage at the Game Developers Conference in 2000 to

formally announce the Xbox. He detailed the future of console gaming

with the Xbox leading the charge. At the time, online gaming on consoles

was both unsuccessful and relatively unknown. The Dreamcast

experimented with a modem adapter, but broadband support out of the box,

a priority for the Xbox from day one, was unheard of. Downloading

additional game content and demos was another foreign concept for

console gamers. Storing this media, as well as music ripped from CDs, on

an internal hard drive was also new. This was a console, we'd play it

on our couch, and we'd use controllers -- but it sure sounded like a

personal computer in terms of what it was capable of.

The original Xbox blurred the line between console and PC.

The original Xbox blurred the line between console and PC.It was important to Microsoft that these PC features and standards not

overshadow the importance of bringing a brand-new console to our

attention. The Xbox design had to look as unlike a PC as possible. After

all, Microsoft was a consumer company in addition to a hardware and

software corporation now. The prototype model shown at GDC in 2000 was a

chrome cube carved into a literal X. It was a dramatic departure from a

computer case, that's for sure. Silly though it may have been, it made a

clear point: Microsoft's Xbox isn't just another gaming system. Things

would be different.

Shortly after GDC, Microsoft cemented its commitment to the Xbox with

its $30 million purchase of Bungie Studios. Its Halo: Combat Evolved

transformed from a Mac/PC third-person shooter to an Xbox-exclusive FPS.

Halo would take advantage of the Xbox's expanded hardware to present an

action game unlike any we'd seen before. The world would be massive in a

way that wasn't possible on other systems. Bungie overhauled the game's

engine to better suit its new platform, and it became the platform's

poster child. The allure of the Xbox was stronger each day leading up to

its 2001 launch.

It was hard not to notice the Xbox, really. With a $500M marketing

budget, Microsoft wasn't pulling any punches with its new device. Demo

kiosks, TV spots, and print ads made up the bulk of Microsoft's

marketing materials. 165 companies had been tinkering with some 2,250

development kits, and the future of the Xbox looked bright in their

hands. In addition to new IPs like Project Gotham Racing and Halo,

Tecmo, Sega, and Capcom showed Japanese support for the platform with

exclusives of their own. Munch's Odyssey and Malice demoed well at the

2001 Consumer Electronics Show as well, where Gates unveiled the final

Xbox model we'd see in fall that year. By E3, we had a release date, a

$299 price-point, and a vague understanding that online gaming would

come after what became a monumental launch for Microsoft.

November 15, 2001 marked the company's first console release, and Halo,

its premier first-party title, shattered software sales records. By the

New Year, the Xbox had sold out nearly everywhere and 1.5 million of the

big, black crates found their way into North American homes. Halo

continued to crush the competition, it was moving full steam ahead. By

April it had cracked one million copies sold, and gained a greater than

50% attach rate.

(Fun fact: Halo sold 5M units by 2005, which was gigantic. How times

change -- in 2011, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 sold 6.5M in its first

24 hours.)

With the Xbox exploding, 2002 looked like a hell of a year. The system

launched in Europe and Japan, and excitement swelled for Splinter Cell,

MechAssault, and The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind. Microsoft made big waves

when it purchased Rare, whose Banjo Kazooie and Goldeneye games were

arguably the pinnacle of Nintendo 64 gaming, for an astonishing $375M.

Oh, and a little sequel called Halo 2 was on the horizon. The industry

was buzzing because of Xbox, and it still hadn't even done what it was

truly meant to do -- we were still only seeing developers scratch the

surface of what great-looking games could really do, and the upcoming

online service had only hinted at its potential. Xbox Live was about to

knock the industry on its ass.

Xbox LIVE was a huge milestone for digital gaming.

Xbox LIVE was a huge milestone for digital gaming.This particular launch wasn't exactly extravagant. At the tail end of

August 2002, Microsoft began its Xbox Live beta test. This whole "online

gaming" thing was so unfamiliar and unproven on consoles it had to be

put through its paces prior to going public. Of more than 100,000

applicants, a lucky 10,000 gained 60 days of early access. Even then,

the limited invitations rolled out in small groups over the course of

those couple months. It had to be done delicately.

Beta testers paid $49.99 for the Xbox Live Starter Kit we'd all see in

November. Along with a headset and a year subscription, which began once

Live went live, users received an online-only demo of the RC car racer,

Re-Volt Live. The Dreamcast port didn't end up on the Xbox after the

test cycle. Weeks later, some time in October, participants also

received MotoGP and Whacked! demos. These also wound up packed in with

the first wave of Starter Kits.

Things looked good by November 15, the Xbox's first birthday, and

Microsoft launched Xbox Live to the masses. In its first week, 150,000

enthusiastic gamers took the plunge and signed up for Xbox Live. 200,000

additional players joined them four months later. Everyone could send

messages and create a unified friends list, which linked to their

Gamertag ID. People were interacting with other human beings from their

living room for the first time, making friends, and experiencing

multiplayer on a new scale. This was a community, not just a bunch of

customers. Oh, and gamers finally had an Xbox controller they could use

effectively. The Japanese "S" model, a smaller, decidedly Dual

Shock-esque version of the game pad, replaced the clumsy, gigantic

"Duke" model permanently.

"Duke" was big, clumsy, and eventually replaced, but some of its design choices remain to this day.

"Duke" was big, clumsy, and eventually replaced, but some of its design choices remain to this day.Over its lifetime, Microsoft's Xbox, despite its success, had some

powerful lows. Bachus left the Xbox team in 2001 (before the thing had

even launched) and Blackley bailed the following year. In 2003, EA opted

against enabling its games for Xbox Live. The mammoth

developer/publisher wasn't keen on the business practice of a

subscription-based online service, so it stuck with Sony. The

PlayStation 2 would be the only place gamers could play Madden online.

This was a harsh blow to Microsoft, but the two companies sorted out

their differences. They reached an agreement in 2004 that brought EA

support to the Xbox online space. This good news came shortly after Ed

Fries, who was responsible for the Bungie and Rare buyouts, left

Microsoft. The Xbox needed a pick-me-up something fierce.

In July 2004, Microsoft hit a huge milestone: Xbox Live had one million

users, 200 pieces of downloadable content, and more than 100

online-enabled titles. An unprecedented digital distribution service

called Xbox Live Arcade was on track for winter as well, and with Halo

2's advertising campaign kicking into full force, the Xbox looked like

it was ready to rock once again.

Halo 2 was an event. The time leading up to the game's release saw the

exposure and marketing storm typically reserved for, well, the launch of

a brand new console. Bungie's sequel had print ads, posters plastered

on public transportation, TV commercials, 7-11 slurpee cups got the

public's blood pumping, while a viral marketing campaign -- the infamous

I Love Bees

-- excited online enthusiasts. It was money and time well, spent,

apparently. On November 9, 2004, Halo 2 generated $125M in sales, based

on nearly 2.5M copies sold, more than half of which were pre-orders. It

destroyed the record its predecessor set. Equally impressive are the

other properties it outdid -- Harry Potter, Spider-Man, and The Matrix

fell beneath Master Chief's big green boots. Halo 2 was the biggest

entertainment launch in history, and it became what Microsoft rightfully

referred to as "a cultural phenomenon."

Halo 2's I Love Bees campaign was an early example of successful viral marketing in the gaming industry.

Halo 2's I Love Bees campaign was an early example of successful viral marketing in the gaming industry.Here's the thing about the Xbox up to this point: It wasn't making any

money. It haemorrhaged cash so badly and for so long that it didn't turn

its first profitable quarter until the back end of 2004. From the

start, the Xbox cost more to make than it did to sell, which is what

makes this so shocking: six months after launch Microsoft dropped the

price by $100 to get more gamers on board with Xbox. It had to rely on

software sales to make bank.

Also, the Xbox was failing in Japan. Not just tanking, either -- it had

died almost instantly. The console's gigantic size, which goes against

the country's small-and-sleek design mentality, is a prime suspect for

its miserable 450,000 sales. Most likely, though, it's the lack of

Japanese developer support, and few games Japanese gamers actually

wanted to play, that killed the brand in Japan. The early dev support

from the east didn't last, and American developers dominated the Xbox

releases. The appeal wasn't there.

With an Xbox successor on its mind behind the scenes for some time,

Microsoft wasn't focusing on its floundering console. When Xbox

manufacturing ceased in 2005, after Nvidia stopped bothering to press

more GPUs, Microsoft was revving up to release the Xbox 360. It made

sense to press on. The Xbox sold respectably well in bursts, but in the

end only 24 million pieces of hardware (16M of which belonged to North

America) moved in its five years. That's half the 50M-units-sold success

Microsoft expected. At the same time, Sony had sold 106 million PS2s.

All told, Microsoft lost an astounding $4 billion -- yeah, with a B --

on the Xbox. That's a lot of money to just leave behind, especially

when the Xbox had so many obvious strengths. It just wasn't able to

capitalize on them like a newer machine could.

In November 2005, just four years after the Xbox hit retail, Microsoft

unloaded the Xbox 360. This time, it would release ahead of Nintendo's

and Sony's newest consoles. Microsoft was the only name on our minds as

we moved into the next generation, giving the successor the early

adopter monopoly. While Microsoft left its failed first attempt behind,

the original Xbox maintained an impressive amount of developer support.

Halo 2, of course, grew into the biggest game on the platform, both in

terms of players and sales. It earned more than 8M sales, and Bungie

released downloadable Halo 2 maps around the time Xbox Live had six

million members. EA, ironically, supported the platform the longest. The

last original Xbox release, Madden 09, landed in August, 2008.

Behold the very last game for the original Xbox.

Behold the very last game for the original Xbox.Although developers migrated their attention to the new Xbox, and many

studios shut down individual game servers over the years,

Counter-Strike, Star Wars: Battlefront, and Halo 2 still had an

impressive, active user-base for years after the 360 came around. The

original Xbox had a heartbeat until April 14, 2010. This day marks the

death of Xbox Live support.

It also marks the moment where we were forced to let go of something

that changed a lot of lives, and turned the industry upside down. The

Xbox was ahead of its time, and Microsoft paid the price for it. While

it failed financially, it was a worthwhile sacrifice for both Microsoft

and the gaming industry. The Xbox had so many important ideas early on

that they've since become the modern standard. This thing changed what

we expect from games. It represented progress and forward-thinking, and

it demanded innovation from its competitors to keep up. This is a

philosophy that carried over to the Xbox 360, and is responsible for

many wonderful things we adore about the industry today.

Thanks for entertaining the idea, Bill.

Similar topics

Similar topics» Fans Petition for Microsoft to Restore Original Xbox One Policies

» Xbox 720 To Feature Blu-Ray Support But Reject Used Games? More Rumors On The Next-Gen Xbox

» Most painful death in Black Ops

» ORIGINAL FALLOUT FOR PC

» Why ‘Real Death’ Beats the Hell Out of Respawning

» Xbox 720 To Feature Blu-Ray Support But Reject Used Games? More Rumors On The Next-Gen Xbox

» Most painful death in Black Ops

» ORIGINAL FALLOUT FOR PC

» Why ‘Real Death’ Beats the Hell Out of Respawning

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum